“There is certainly no man in Boston better equipped for painting and for teaching how to paint, the human figure, than Tommaso Juglaris . . . In the scores of sketches and studies which cover the walls are shown from what variety of position the draughtsman has observed the human figure---now seizing its complete contours, and now confining his attention to a single limb, to a turn of the head, a pose of the torso, a gesture of a hand—now studying muscle and artery, bone and tendon . . . wherever one looks he sees the same mastery of the human figure.” —“The Art Galleries” (Undated Review, Juglaris Album)

“I had become the professor of all the painters in Boston. In addition to the good pay, it was a place of honor that raised me immensely in the public’s consideration.”

America had long looked to Europe, particularly France, for its artistic standards. Legions of American artists studied abroad. However, in Boston during the 1880s there was a need for the same training more conveniently at hand. Given Tommaso Juglaris’s talents, boldness, and Beaux Arts credentials as an acknowledged Paris Salon painter, there were many aspiring students, including women, interested in studying with him. Accordingly, from his earliest days in Boston, Juglaris offered private lessons to select students. This continued even after he won his respected position as a teacher-in residence at the Boston Art Club. Indeed, following the example of his Boston friend and colleague John Ward Dunsmore, Juglaris actually advertised in Boston newspapers the opening of a “Tommaso Juglaris Art School” with “Life and Costume Classes Daily” and “Figure” as a “Specialty.” (Boston Evening Transcript, March 27, 1883, 3; September 15 and November 10, 1886, 5, 7)

Juglaris’s initial studio and instructional space was located on the third floor of a six-story building at 161 Tremont Street. It was owned by Mary Goddard, who with her husband, Thomas, funded the construction of the Tufts College Chapel where Juglaris was commissioned to design several stained glass windows. (“Local Fires,” Boston Evening Transcript, May 7, 1883, 7) However, when an all-building fire in early May 1883 completely destroyed his Tremont Street studio, Juglaris relocated nearby to 50 Bromfield Street, a hundred feet from the gate to Boston’s Old Granary Burying Ground on Tremont Street. Happily, the new space was also large enough to accommodate students. Fellow tenants in the Bromfield Street building included a leading Boston commercial photographer, Charles Henry Currier, and a photography supplies firm, operated by John H. Thurston. Additionally, the Society of Amateur Photographers, also known as the Boston Camera Club, maintained their headquarters upstairs, complete with an exhibition gallery and a room fully equipped with the latest in stereopticon technology. If his neighbor’s stereoptican equipment ever became available to him on loan, Juglaris may have found it professionally helpful in both executing larger mural commissions and instructing students. (“The Fine Arts: Thomas Juglaris’ Studio Exhibition,” Boston Evening Transcript, March 31, 1890, 6)

Not content to rest on his laurels as either Boston Art Club “professor” or private studio instructor, Juglaris welcomed an 1883 invitation to artistically head the new Cowles Art School. Originally organized by Frank Cowles one floor above Juglaris’s studio in the ill-fated Tremont Street building, it quickly found a new home in the New Studio Art Building at 145 Dartmouth Street along the edge of the Boston Commons. As administered by Juglaris and Cowles jointly, the freshly re-launched school was, in the words of one art critic, an “alive and alert” place. It compared very favorably to the more resource-rich, yet rather staid and hide-bound, Boston Museum School in Copley Square. (“Boston…The Art Museum School and Mr. Cowles’s Art School,” Manufacturer’s and Farmer’s Journal [Providence, Rhode Island], October 12, 1885) As art historian Catherine L. Holmes notes: “Here [was] offered watercolor, still-life, modeling, composition, perspective, artistic autonomy, sketching and separate men’s and women’s life classes. In a departure from other art schools, Cowles also offered more liberal arts courses in French language, literature, and art history. Fulfilling Mr. Cowles’ intent, the school was referenced as the ‘Julian’s of Boston’ because its teaching was informal and emphasized life and modeling classes and served as a connection to Boston artists studying in France.”

Geared to talented but life-challenged students, struggling—not unlike a younger Juglaris in Turin and Paris--to gain the art education needed to pursue a full art career, classes were available morning, afternoon, and night, as well as on Saturdays and during summers. With Juglaris as “principal” the standing and adjunct instructional faculty included Robert Vonnoh, Mercy A. Bailey, James Harvey Young, Ernest Longfellow, Henry Hitchings, and Edgar Parker. Of course, Longfellow, son of the famous poet, was already a Juglaris compatriot dating back to their mutually shared days as disciples of Thomas Couture outside Paris. Likewise, Hitchings, Director of Drawing for Boston Public Schools, had cause, then and later, to collaborate with Juglaris beyond the portals of the Cowles Art School in the latter’s extra role as a state-appointed assessor of art curriculum for public classroom use. (Advertisement, Boston Evening Transcript, February 21, 3, and March 7, 1885, 7) Meanwhile, Juglaris knew Edgar Parker no less well: mostly a portrait painter with several works hanging in Boston’s Faneuil Hall, Parker enjoyed further local eminence as president of the Boston Art Club.

Although Juglaris resigned his principalship at the Cowles Art School in early October 1886 over pay and accounting issues, his influence lingered, foundationally contributing to the “atmosphere of the old-world masters’ schools which permeates every nook and corner of this institute.” (Frank Robinson, The Art Interchange 34/1 (New York: January 1895)) Significantly, Juglaris was succeeded as Cowles Art School’s chief instructor by Dennis Miller Bunker, newly returned from five years of Beaux Arts training in Paris.

By this time Juglaris had a well-established reputation as both artist and art educator across New England and beyond. Indeed, as the local press testified, he had emerged as “one of the most successful art teachers in Boston” and “most distinguished art instructors in the country.” (“The New Teacher of the School of Design,” August 19, 1886, 6, and “At the School of Design,” January 19, 1888, 8, Providence Journal) Certainly indicative of this, Juglaris was called upon to serve as a juror for art competitions at the National Academy of Design in New York City and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia where on other occasions he also exhibited his own paintings.

Not surprisingly, a full year before his departure from the Cowles Art School, Juglaris was wooed by the founders of the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence to join their faculty. Despite the fifty-mile distance from Boston and the attendant train commute, he agreed to do join the RISD staff, beginning in fall 1886. But Juglaris’s embrace of new assignments did not stop there. In 1888, two years after resigning from the Cowles Art School and starting up at RISD, he accepted yet another teaching post at the New England Conservatory of Music.

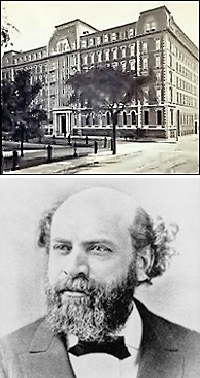

Founded in 1867, the New England Conservatory of Music had originally met in rooms at the Boston Music Hall. However, in 1882, the Conservatory, which enjoyed a nominal affiliation with Boston University, acquired the St. James Hotel at Franklin Square in the city’s South End and embarked on a substantial expansion. Built on adjoining land was a large recital hall, which soon hosted hundreds of concerts and student performances annually. As part of its ambitious vision, the Conservatory also decided to open under its own auspices a school of fine arts. At the behest of the New England Conservatory’s founder and president, Dr. Eben Tourjee, Juglaris was recruited to help anchor and lead it, adding stature to the school’s nascent art and design program. As Dr. Tourjee informed the Boston Daily Globe and its readership in remarks published September 13, 1888: “The new feature of the year most worthy of note is the opening of the school of fine arts, with T. Juglaris as instructor in drawing and painting. The connection of this gentleman with the institution will greatly benefit the students, a large number of whom have stated their intention of pursuing one or more branches of the arts.” As an extension of his role at the New England Conservatory, Juglaris became a presence in the South Boston community. He participated in the annual exhibition of the South Boston Art Club at the local Bethesda Hall, organized by club president and marine painter Willam Lofthouse Dean. (“The Fine Arts,” Boston Evening Transcript, May 6, 1891, 4) In April 1891 Juglaris was also commissioned to paint a series of murals for the commanding edifice of South Boston’s Saints Peter and Paul Catholic Church on West Broadway Avenue.

At the end of the 1880s and the start of 1890s Juglaris thus proved to be a very busy man, dividing his time between the Boston Art Club academy, the Rhode Island School of Design, and the New England Conservatory, while still privately teaching students and advising the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on public school art curriculums. To an extent far beyond anything he may have originally imagined and anticipated, Juglaris had truly become “the professor of all painters in Boston.”